How true! I first learned of boundaries while working at a health clinic for the homeless. Every day they would gather at the door before morning, while inside we set up the ropes that organized their need into orderly rows and straight lines. One November I met a girl with an abscessed tooth and we ended up sleeping together for three weeks; for almost twenty-one days I sheltered her in the white sheets of my bed while the bungalow shuddered under a rainstorm that turned the lawn to mud and elsewhere washed entire towns away. On the twenty-first morning she was gone. I later heard from the line that she had gone back to the subway and had a baby and never wanted anything from the day-lit world again.

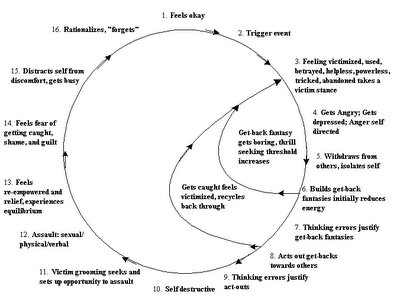

You learn to live without love, if you work at it hard enough. For one thing the bed is all yours and the stars never sting and even a particularly good song will pass right through you, it gets that simple. Years went by before I found myself working as a re-educator for sexually criminal youth. “You can learn to live without love, if you work hard enough,” I taught them, and they all took notes. They had to; their P.O.s were always in the back of classroom, tapping their billy-clubs as a reminder of what waited for those who failed my class -- which was prison, of course, and secretly I think each P.O. believed that anal or oral penetration behind bars was the only effective treatment for these youth (who were deviants, let there be no doubt; but also often illiterate and very few passed, despite my best intentions). “What is the offense cycle?” I would ask them, and then drew it on the board like this:

Once every few months, a particularly aggressive youth might ignore the P.O. tapping behind him and ask how knowing the offense cycle did him any good at all. My supervisor warned me about this kind of youth, and gave me the correct response, which I would dutifully relay to the class. “Learning the offense cycle is important,” I began, “for four reasons: 1) It makes the youth’s behavior predictable by bringing it into full consciousness; 2) It proves the youth can be extremely self-observant; 3) It enable the youth to experience vulnerability as a positive and empowering experience; and 4) It provides an experience of nonsexual intimacy and personal self-control, which ultimately helps the youth to abandon the secrecy of his self,” this latter point never failing to get grins and nods from the officers in the back.

If I don’t regret my choices, then I must not regret the life I made of them: my re-education days are long gone and somehow the months have slipped into comfortable repetition, like white sheets or a sleeping body breathing in time to secret rhythms. Most nights I remember my dreams, but come morning I am too busy to write them down: I have subways to catch, bills to pay, friends to phone and meals to eat. There is always work to be done. “Remind me,” K. says, “because sometimes I forget where I end and others begin.”

“It is no problem,” I reply. “First figure out what you most need -- then take a rope and split it in half. Now all you have to do is choose which side you will spent your whole life wanting, and which side you will just call home.”

-amr-